Ma Defan is a fine artist, costume designer and artist of China Film Group. She graduated from School of Fine Arts of Tsinghua University and is currently based in Beijing. The Artist believes that “Art is Dialogue.” She crosses various fields from film costume design to calligraphy creation, awakens the interlocutor’s appearance through creation, sends communication requests on mountains, water, and climate, and connects nature, everything, inner, and emotions with art. In recent years, the focus of her art has shifted to the field of modern calligraphy and installation, with brush and ink as the core, showing a broader contemporary perspective.

Interview with the Artist

You once said, “Art is dialogue.” Who—or what—do you most often find yourself in dialogue with?

When I say “art is dialogue,” it is a dialogue with nature and a dialogue with myself. For example, in my current Twenty-Four Solar Terms project, I create works in natural environments on the exact day of each solar term. Each piece becomes a conversation—with nature, with language, with time, and with myself.

你曾说过“艺术是对话”。你觉得你最常在与谁,或什么,进行对话?

“艺术是对话”,我和自然的对话、和自己的对话。如当下做的“二十四节气”课题,每个节气的当天在自然环境中创作二十四节气系列与自然、文字、时间、自己的一场对话。

You often create barefoot outdoors with large, expansive movements. Is this kind of creation driven more by the body or guided by the mind?

Creating barefoot is a completely natural, instinctive action—an impulse, a sensation. During the process, what matters most is embodied feeling: sensing the earth, plants, the breath of the air, its temperature and humidity. These subtle signals are more trustworthy than any concept. In short: “the truth of the body, the measure of intention.”

你经常赤脚在户外创作,动作幅度很大。这种创作更受身体的驱动,还是头脑的指引?

赤脚创作,是一个纯粹的自然而然的动作、想法,感受。创作的过程中更多的是切身的感受,感受土地、草木、空气的呼吸、凉热、湿度,这些微小的讯号,比任何概念都更可靠。简言之“身的真实”,“意的分寸”。

Your work contains both spirituality and physicality. Do you see it more as a meditative process, or as an active act, like performance?

My practice might be described as “stillness within action.” It is a deeply subjective, personal act—not a performance designed for viewing. It’s more like an exchange with nature, an emotional outpouring, a process of co-creation with the natural world. My practice is active, yet it unfolds from the inside out.

你的作品既有精神性也有身体性。你认为这更像是一种冥想的过程,还是一种更主动的行为,比如表演?

我的创作可能像“行动中的静修”。它是一个很主观的个人行为,不是为观看而设置的表演,更像是和自然的一个交流、情感输出,和自然共同参与这个创作的的过程。是主动的,也是由内而外的。

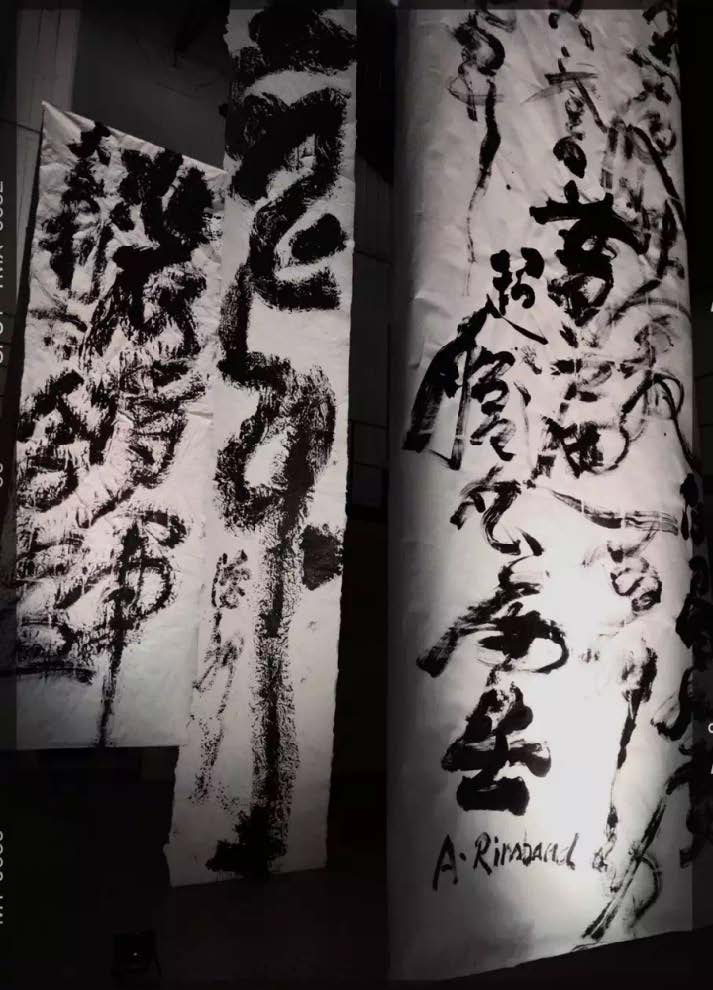

Many of your calligraphy works are created on natural fiber textiles placed directly in nature—almost as if ink flows through soil or snow. How does nature influence your writing?

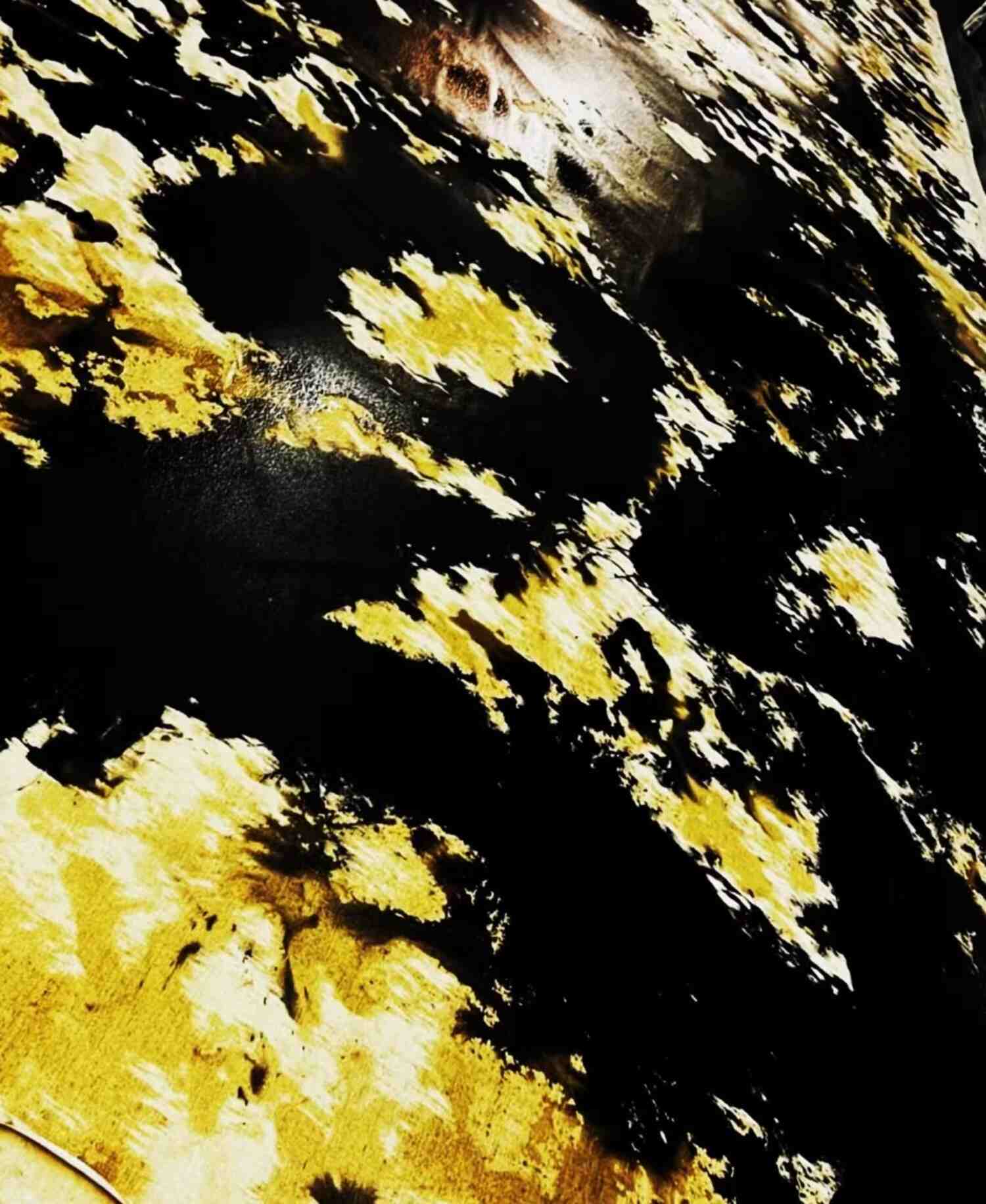

Nature is both the site and a collaborator. The heat of the sun, the granularity of soil, the soaking of rain, the crystalline structure of snow—all leave unrepeatable traces within the fibers of the cloth. Hemp, ramie, and cotton each absorb ink differently. Their weaves resemble invisible riverbeds, guiding the ink’s movement.

你的许多书法作品是在自然纤维布料上创作的,直接放置在大自然中——就像墨流穿过土地或雪地。大自然是如何影响你书写的?

自然既是场所,也是合作者。太阳的炙热、土壤的颗粒、雨水的浸染、雪的晶体,会在布的纤维里留下不可复制的路径。麻、苎、棉各自的吸附性不同,织纹像隐形的河道,牵引墨的走向。

Some of your works exist only briefly in nature before being removed or altered. How do you understand the role of impermanence in your practice?

Impermanence is both the destiny of my work and its home. Many forms exist only fleetingly on site—wind rewrites them, rain carries them away, sunlight transforms them into other colors. What remains may only be images, fragments, or momentary memories.

有些作品只在自然环境中短暂存在,随后被移走或改变。你如何看待“无常”这个概念在你创作中的角色?

无常是我作品的命运,也是它的归属。许多形迹只在现场短暂存在——风会改写它,雨会带走它,日光会把它晒成另一种颜色。留下来的,可能只是影像、碎片或短暂的记忆。

You have developed two distinct personal styles: pictographic writing and left-hand writing. Why did you explore these approaches, and how do they feel different in practice?

Pictographic writing comes from my original curiosity about characters themselves. Chinese characters originated as images—mountain, water, wood, sun, moon—where form and meaning overlap. I want to pull language back to its “first sound,” allowing viewers not only to read meaning but to see its energetic form.

Left-hand writing feels more like a child’s gesture. The right hand carries too much training and habit, easily constrained by so-called “skill.” With the left hand, lines are often more primal. Their rawness and awkwardness give the characters a kind of wild vitality.

你发展出两种个人风格:象形书和左手书。你为何想尝试这些风格?在书写时它们的感觉有何不同?

象形书源于我对文字最初的好奇:汉字本就是从图像出发的,山、水、木、日、月,都是形与意的交叠。我希望把文字重新拉回它的“初声”,让观者不仅读到意义,还能直观地看到它的形态能量。左手书则更像一个孩子。右手有太多训练和习惯,容易受制于所谓的“功力”。换到左手,线条常常更本真,那种生涩、笨拙却让字带着一种野性。

Do you see your writing as text, image, or something in between?

For me, it is neither purely text nor purely image, but a kind of “trace.” Take the character yi (一): it is the simplest symbol, yet also a horizon line, the length of a breath. Its visual effect and linguistic meaning are inseparable. I hope viewers can feel the tension even without knowing the language—just as one can be moved by music without understanding the lyrics.

你认为你的书写是文字、图像,还是介于两者之间的东西?

对我而言,它既不是纯粹的文字,也不是纯粹的图像,而是一种“痕迹”。比如“一”这个字,既是最简单的符号,也是地平线、呼吸的长度。它的视觉效果和语言意义交织在一起,无法分割。我的书写希望观者在不识字的情况下也能感受到张力,就像听不懂歌词的人依旧能被旋律打动。

How do you choose the words or phrases you write? Are they planned in advance or improvised?

Sometimes they are premeditated—solar terms, lines from scriptures, fragments of poetry. These texts already carry deep cultural resonance; I simply offer them as emotional anchors for the ink. More often, however, they arise spontaneously. When the body enters a particular environment, words surface on their own—like calls from the subconscious. I trust improvisation; it is often more sincere and direct than careful deliberation.

你是如何选择写下的词语或短语的——这些是事先计划好的,还是即兴创作的?

有时候是预先构思的词——比如节气、经文里的句子、诗词里的短语;这些文字本身已经带有深厚的文化气场,我只是借它们为墨寻找情感的落脚点。但更多时候是即兴的:当身体进入某种环境,字句会自己跳出来。像潜意识里的呼喊,不需要事先准备。我相信即兴的力量,它往往比深思熟虑更真诚、更直接。

Your work feels deeply contemporary yet clearly rooted in calligraphic tradition. Are you trying to break away from tradition, or reshape it from within?

I have never wanted to “escape” tradition. Tradition is like a deep river—turn away from it, and you lose your source. I prefer to let the river flow in a different direction. Calligraphic tradition taught me how to move the brush and enter the paper, but I do not wish to stop at reverence for technique. I want to awaken its vitality, allowing it to breathe within a contemporary context. Reshaping is not confrontation; it is continuation.

你的作品非常当代,但又显然扎根于书法传统。你是在试图摆脱传统,还是在从内部重塑它?

我从未想过“摆脱”传统。传统像一条深河,你若背离它,脚下就会失去水源。我更愿意说,我是让这条河换一种流向。书法的传统教会我如何运笔、如何入纸,但我不愿仅仅停留在“技法”的敬仰。我更想把传统的生命力重新唤醒,让它在当代语境中继续呼吸。重塑不是对抗,而是续命。

In your Twenty-Four Solar Terms series, you create a calligraphic response for each term. What led you to connect your work so closely with time and climate?

The solar terms represent the most nuanced way the Chinese perceive time—far more attuned to the body and the land than the Gregorian calendar. The wind of Beginning of Spring, the scent of wheat at Grain in Ear, the cool dampness of White Dew—all deeply shape breathing and inner states. Writing the solar terms allows my work to synchronize with nature’s respiration. Time is not abstract; it has temperature and color. Each solar term is a poem. Writing them is both a handshake with time and a reminder of where my body and heart reside.

在你的《二十四节气》系列中,你为每一个节气创作了书法回应。是什么促使你将作品与时间与气候如此紧密地联系在一起?

节气是中国人最细致的时间感知方式,它比公历更贴近身体与土地。立春的风、芒种的麦香、白露的湿凉,这些感受深刻影响着人的呼吸与心境。我写“二十四节气”,是想让作品成为与自然的呼吸同步的注脚。时间不是抽象的,它有温度和色彩。每一个节气就是一首诗,书写它们,我既是在与时间握手,也是在提醒自己:身处何时、心在何处。作品因此不再只是墨迹,而是一个个季节存留的故事。

When you work outdoors, are weather conditions—wind, cold, sunlight—challenges or integral elements of creation?

They are collaborators, not obstacles. Wind alters the ink’s trajectory, producing unexpected lines; cold makes the body tremble, tightening or hastening movements, leaving tremors in the texture of the characters; sunlight constantly shifts shadows, giving the same work different moods over time. When the wind snaps the cloth in the air and ink merges with atmosphere, what I feel is not merely writing, but an expression of self aligned with circumstance.

当你在户外创作时,天气——比如风、寒冷、阳光——是挑战,还是创作的一部分?

对我来说,天气不是阻碍,而是合作者。风会改变墨迹的轨迹,让线条生出意料之外的变化;寒冷会让身体颤抖,动作更急促或更收缩,那些抖动会留在字的肌理里;阳光则是很奇妙的,它不断改变光影,让同一幅作品在不同时间段展现出截然不同的气息。当风把布料吹得猎猎作响,墨迹和空气在那一瞬间混合在一起,我感受到的不只是书写,而是一种随心自我的表达。

You document many works through photography and video. Are these simply records, or part of the work itself?

At first, they were a documentation, many works are quickly taken by nature, fading or being covered. Gradually, I realized that image and video enter the trajectory of the work itself. They are not byproducts, but alternative perspectives. For instance, when I write on snow, the ink soon dissolves; what the eye sees fades, but the camera captures the process of disappearance. That process becomes part of the work. The images preserve not only results, but the passage of time. For viewers, photographs or videos may be all they see, yet within them exist wind, cold, and fleeting presence. The image allows more people to encounter impermanence. I now see it as an extension of the work.

你用摄影和影像记录了许多作品。这些只是记录,还是作品本身的一部分?

一开始,影像只是记录,因为很多作品会很快被自然带走,或褪色,或被覆盖。但渐渐地我意识到,摄影和影像本身也进入了作品的轨迹。它们不是“副产品”,而是另一个视角的呈现。比如,当我在雪地上书写,墨迹很快被融化的雪稀释,肉眼中的作品逐渐消失模糊,但镜头捕捉到它消逝的过程,这个过程本身也成为作品的一部分。换句话说,影像不仅保存了结果,更保存了流逝的时间。对于观众来说,也许他们看到的只是照片或短片,但其中包含了风声、寒意和瞬间的气息。这些是现场观众才能直接感受的,而影像让更多人能与那份“无常”相遇。所以,我现在更愿意把它看作作品的延伸。

Even when you create alone, your movements have performative qualities. Do you consider the presence of an audience?

When I lift the brush, I enter a state of forgetfulness—only a dialogue with nature remains. Large movements require rotation and shifting center of gravity; these arise from physical necessity, not spectacle. Later I realized that even without human viewers, heaven and earth are witnesses—wind, trees, stones, sunlight all observe and participate. If people are present, they simply join the dialogue. I am not performing; I am engaging in a complete bodily conversation that may appear performative to others.

即使你常常是独自创作,你的动作也带有表演的特征。你在创作时会考虑观众的存在吗?

在创作时,当我拿起笔的瞬间,会是一种忘我的状态,只是和自然的对话。当我挥动大笔,身体必须旋转,重心必须跟随,这是自然力学的需要,而不是观赏性的安排。可是后来我发现,即使没有观众,天地也是观众——风、树、石头、阳光,它们见证了动作并参与其中。人类的观众若在场,也只是加入了这场对话。所以,我更愿意说,我并没有在“表演”,而是在进行一次彻底的身体对话;只是旁人看到了,会觉得那像是一场表演。

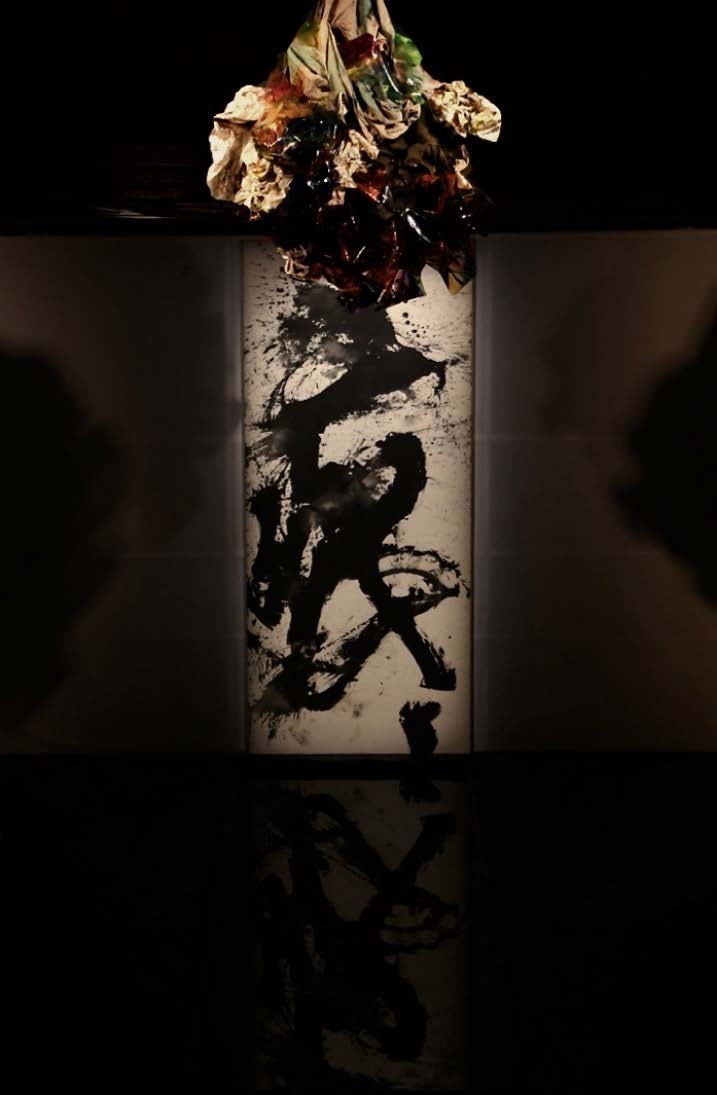

You often use discarded or recycled materials in textiles and garments. Is sustainability important to you?

Yes, but for me sustainability is more than environmentalism—it is a philosophy of life. Discarded fabrics, old clothing, forgotten sacks carry traces of time and human warmth. Using them gives them a second life. This regeneration is not merely about saving resources, but about confronting impermanence and continuity, and reexamining what “beauty” truly means in life.

你在纺织品和服装作品中经常使用废弃或再利用的材料。可持续性对你来说是一个重要的概念吗?

是的,可持续性对我来说不仅是环保概念,更是一种生命哲学。废弃的布料、旧衣物、被遗忘的麻袋,它们承载了时间的痕迹,也带有人的体温和生活的气息。当我用它们来创作时,其实赋予它们第二次生命。这种再生不是为了“节约”而已,而是让我和材料共同面对“无常”与“延续”的辩证,重新审视生命本我“美”的含义。

What draws you to fibers and soft materials as writing surfaces, rather than paper or canvas? Does texture influence your writing?

At first, rice paper tore too easily. Through experimentation, I discovered that fiber and soft materials—hemp, cotton—have undulations, frayed edges, coarse weaves. When ink lands, fibers absorb, resist, and overflow. This instability mirrors my pursuit of the uncontrollable. Their softness allows my body to engage more fully: I can spread them on the ground, drag, swing, fold them. They become extensions of the body.

是什么吸引你选择纤维和柔软材质作为书写的载体,而不是纸或画布?这与你书写时材质的纹理或行为有关吗?

期初的原因是宣纸很容易被写破,后来尝试了很多材料,发现纤维与柔软材质麻布、棉布,它们有起伏、有毛边、有粗糙的织纹。当墨落下去,纤维会吞咽,会抗拒,也会溢出。这种不稳定性恰好对应了我对“不可控”的追求。布料的柔软,让我能以身体更大幅度地介入——我可以在地面铺开,可以拖拽、甩动、折叠,它们像身体的延伸。

You have worked across fashion, film, installation, and design. What connects these different forms, and how do they influence one another?

Rather than separate fields, I see them as branches of the same vein. Whether clothing, film, calligraphy, or installation, the essence is how form and emotion resonate. Fashion sharpened my sensitivity to the relationship between fabric and body. Film taught me the power of narrative—even a static work can contain temporal progression. Installation redefined my understanding of space—characters no longer remain flat, but breathe with their surroundings. These experiences interpenetrate, allowing me to approach art holistically as a language of dialogue with the world.

你曾涉足服装、电影、装置和设计等多个领域。是什么将这些不同形式联系在一起的?一个领域的创作如何影响了另一个?

我觉得把这些看成不同领域,不如看作同一根脉络的分支。无论是服装、电影,还是书法、装置,本质都是“如何让形象与情感发生共鸣”。服装训练了我对面料与身体关系的敏感:布料如何贴合皮肤,如何随着动作变形。电影让我懂得“叙事”的力量:即便是一件静态作品,它也可能像镜头一样带有时间的推进感。装置让我重新思考空间:字不再只是二维的平面,而是与周遭环境共同呼吸的存在。所有这些经验互相渗透,让我不必拘泥于某一门类,而是以整体的方式去理解艺术——它们都是一种“与世界对话”的语言,只是媒介不同。

You have shown work in cities like Beijing and Paris. How do audiences there respond to such quiet, nature-based works?

In Beijing, audiences often arrive with expectations rooted in calligraphic tradition, searching for technique and stylistic lineage. In Paris, viewers enter more directly through sensory and spatial experience; they may not understand the characters, but feel the tension of the ink. Both responses interest me. One is a return to tradition moving toward the contemporary; the other enters the contemporary through unfamiliarity. In Paris, someone once said the works felt like watching wind move through trees; in Beijing, someone said the characters reminded them of the smell of earth from their rural childhood.

你曾在北京和巴黎这样的城市环境中展示作品。这些地方的观众如何回应如此安静且与自然紧密相连的作品?

在北京,观众常常带着对书法传统的期待来看,他们会先寻找技法、风格上的线索;在巴黎,观众则更直接地从感官和空间去进入,他们可能看不懂字意,但会被字的墨迹的张力打动。两种观众的回应都让我感到有趣:前者是“回望传统再走向当代”,后者是“从陌生直入当代”。我记得在巴黎,有人说,看这些作品就像看风吹过的树林;在北京,有人说,看这些字让他们想起童年在乡下的泥土味。

Do you see yourself as part of an artistic community, or as carving out your own space?

Strictly speaking, I do not strongly belong to any particular community. I value “independent breathing.” My work often requires solitude—quiet, and direct dialogue with nature.

你认为自己属于某个艺术社群吗,还是在开辟一片属于自己的空间?

严格来说,我并不强烈归属于某个社群。我更看重的是“独立的呼吸”。我的创作很多时候是孤独的,它需要安静、需要和自然直接对话。

If you could install a work anywhere in the world, without limitation, where would it be, and what would you write?

Wherever I go, in any place, I hope to write down my response to nature and nature’s response to me, leaving it there. That is enough. Humans are merely passersby between heaven and earth, and art is also a passerby.

如果你可以在世界上任何地方安装一件作品,没有任何限制,你会选择哪里?你会写下什么?

我希望不论走到哪里、任何地方,我对自然的感受以及自然给予我的感受,书写记录下来,留在那里,仅此足以。人在天地之间只是过客,艺术也是过客。

more Art content here

Our next event : Säule, Berghain – 15.01.2026 click here