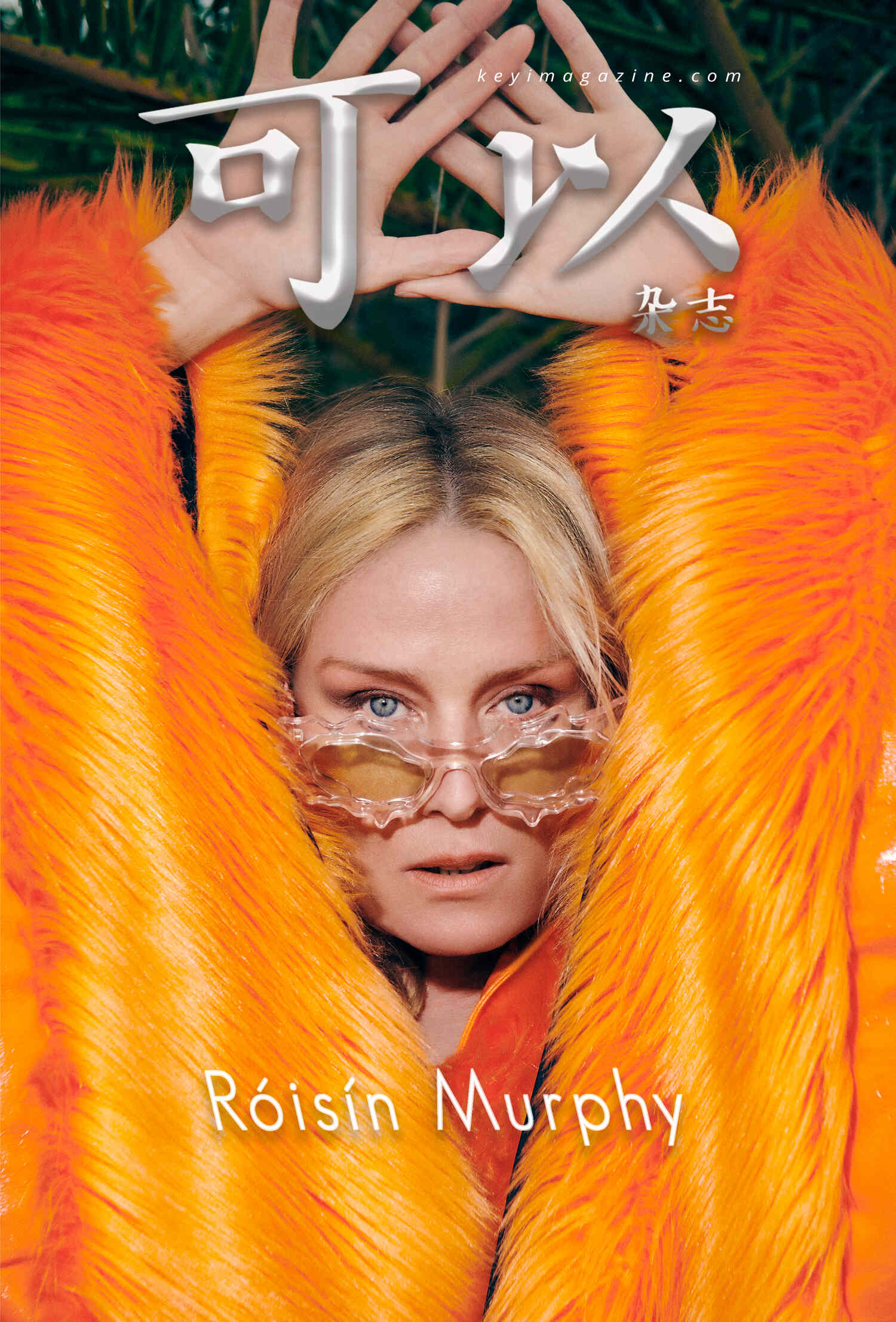

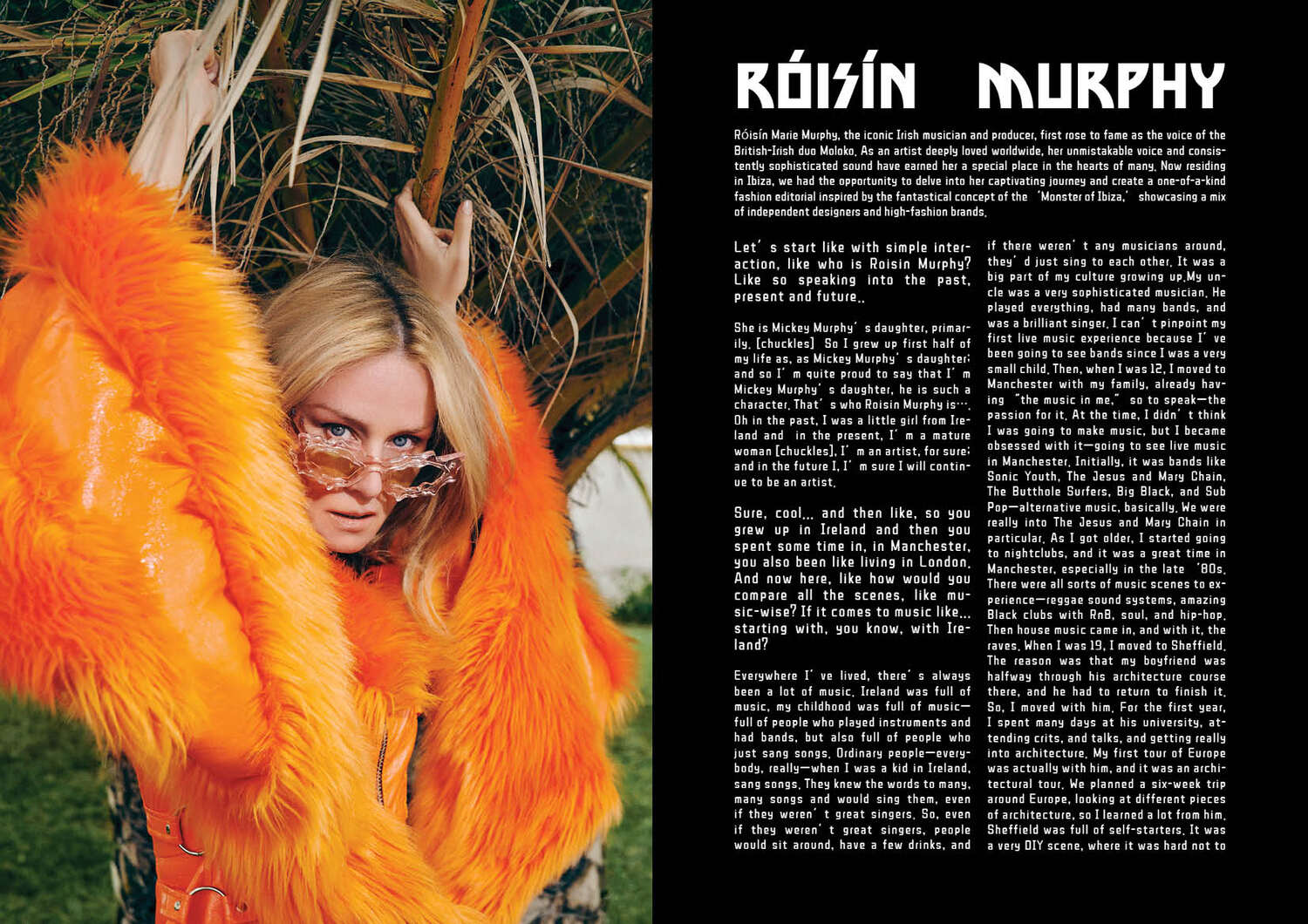

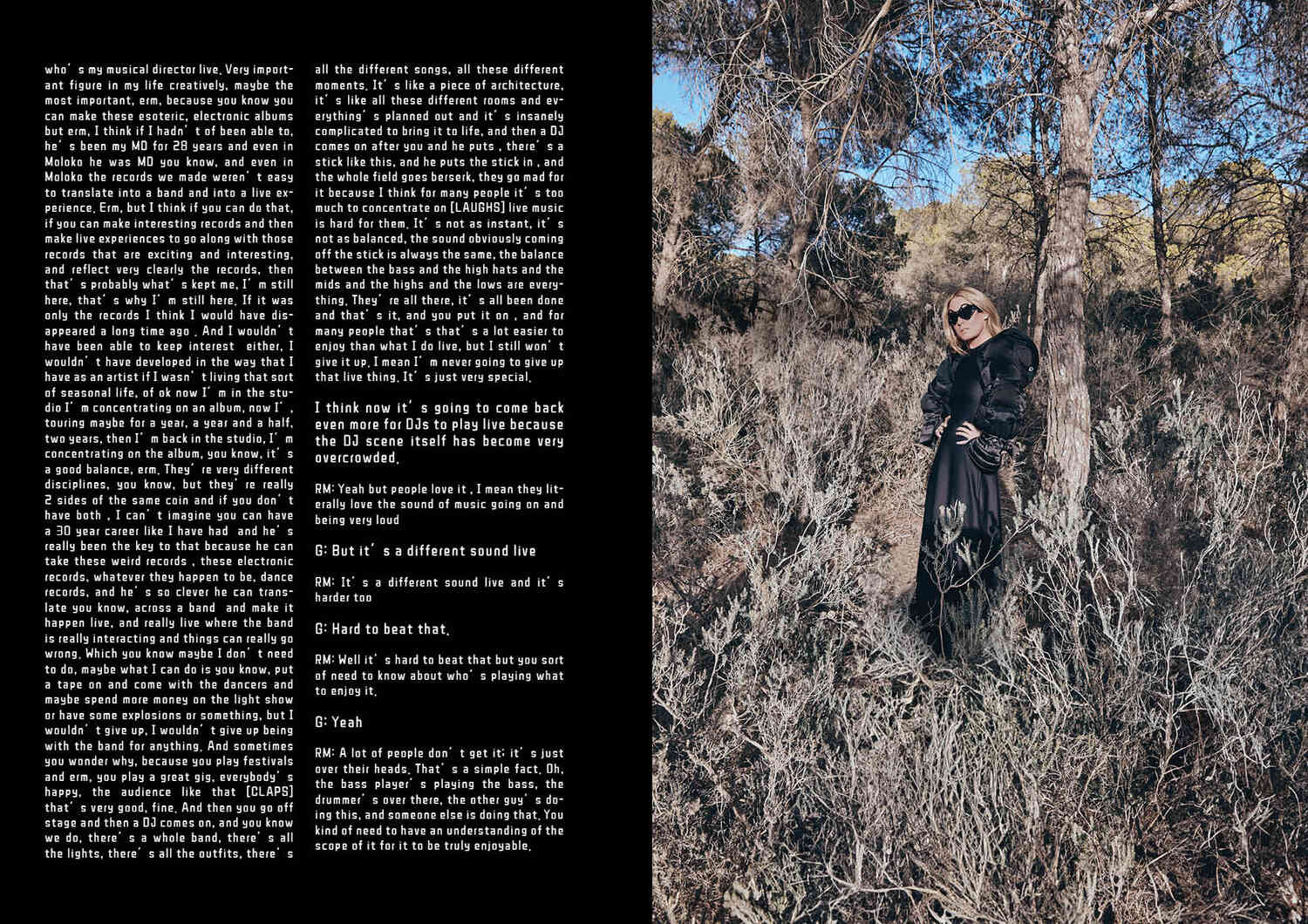

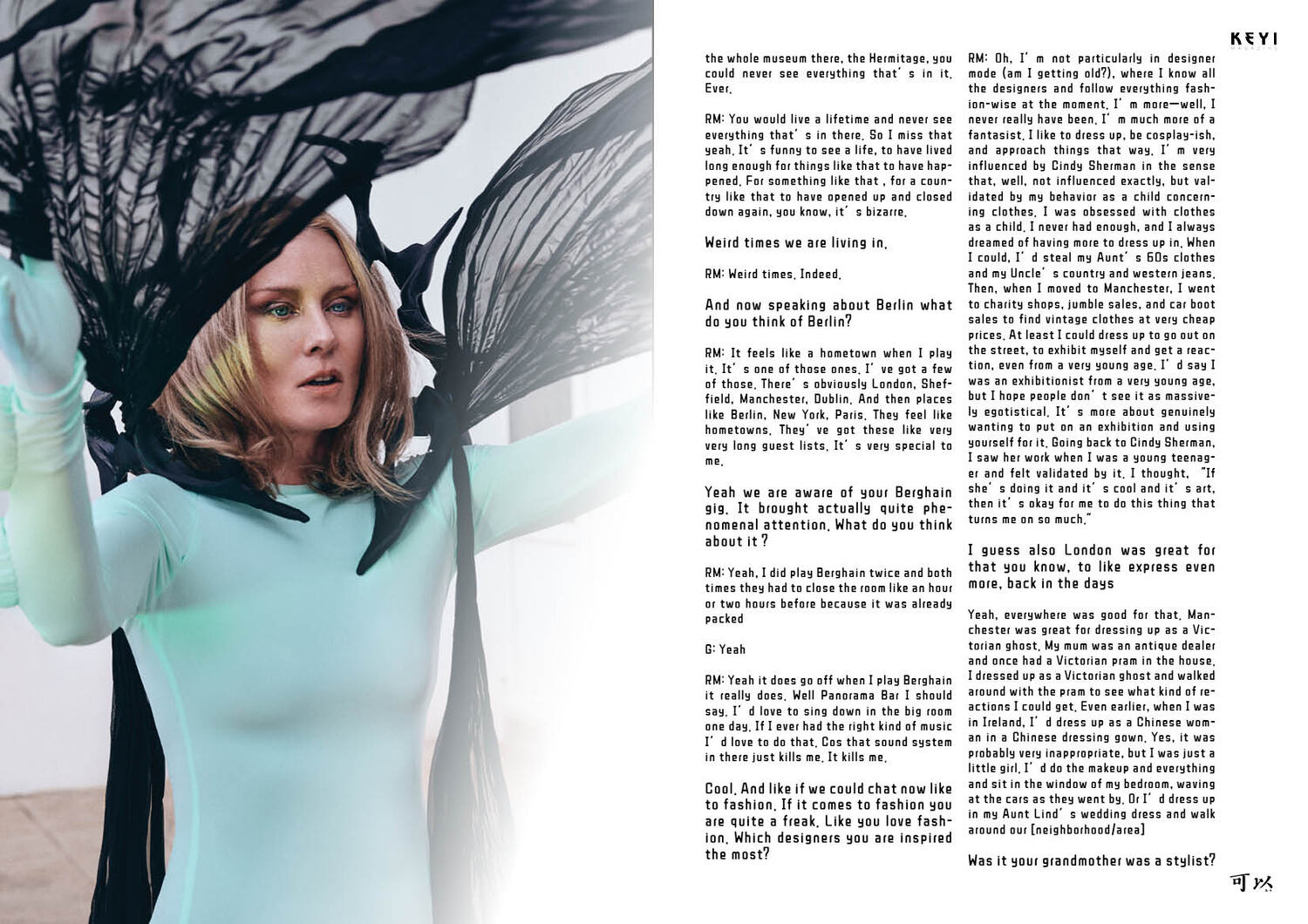

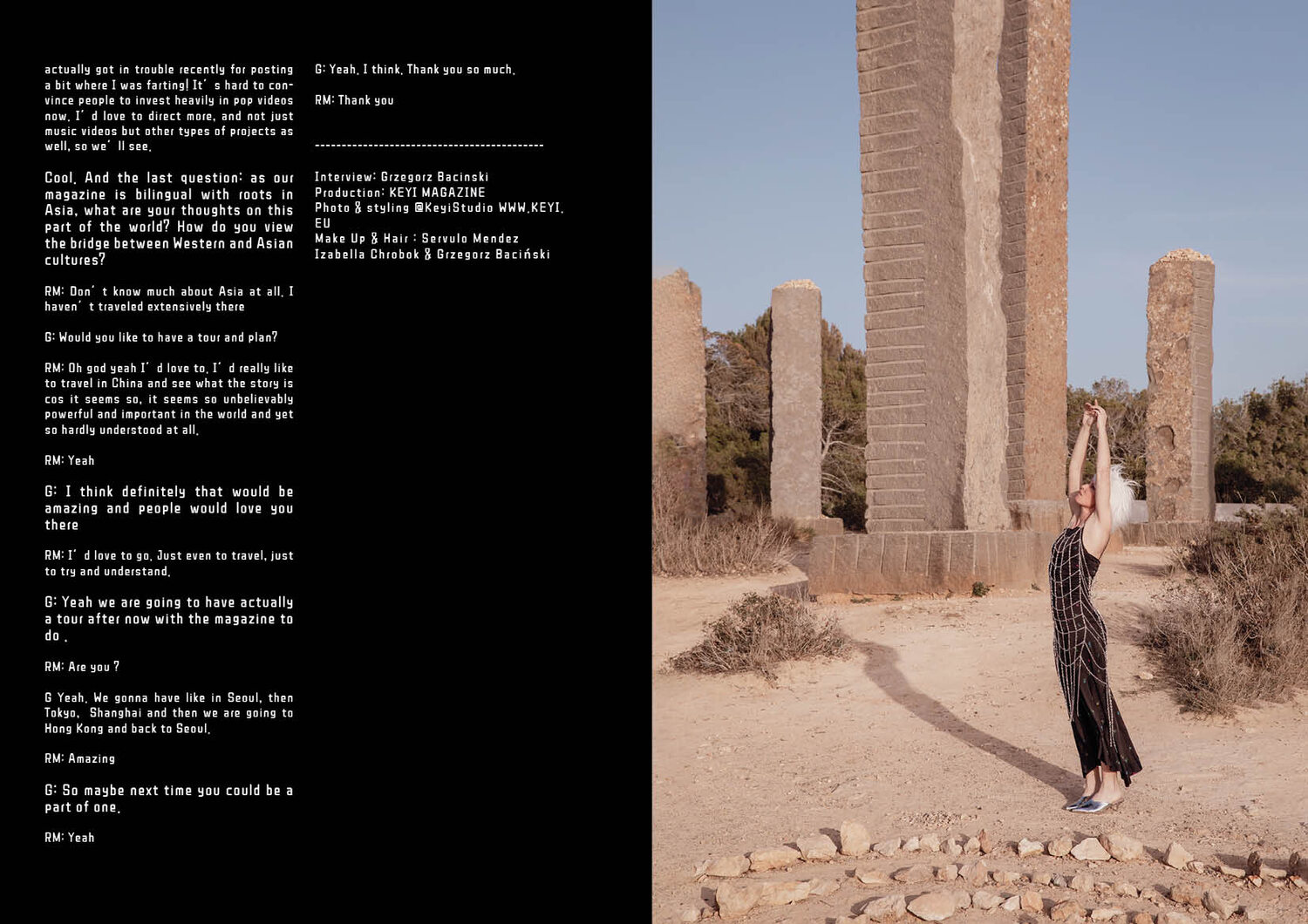

Róisín Marie Murphy, the iconic Irish musician and producer, first rose to fame as the voice of the British-Irish duo Moloko. As an artist deeply loved worldwide, her unmistakable voice and consistently sophisticated sound have earned her a special place in the hearts of many. Now residing in Ibiza, we had the opportunity to delve into her captivating journey and create a one-of-a-kind fashion editorial inspired by the fantastical concept of the “Monster of Ibiza,” showcasing a mix of independent designers and high-fashion brands.

Let’s start with a simple question: Who is Róisín Marie Murphy?

If we look at it in terms of past, present, and future…

She is Mickey Murphy’s daughter, primarily. [chuckles] I grew up, for the first half of my life, as Mickey Murphy’s daughter. I’m quite proud of that—he is such a character. That’s who Róisín Murphy is.

In the past, I was a little girl from Ireland. In the present, I’m a mature woman [chuckles], and definitely an artist. In the future, I’m sure I’ll continue to be an artist.

Sure, cool. And then, you grew up in Ireland, spent some time in Manchester, lived in London… and now you’re here. How would you compare all these scenes, especially musically? Starting with Ireland?

Everywhere I’ve lived, there’s always been a lot of music. Ireland was full of it—my childhood was full of music, full of people who played instruments and had bands, but also full of people who just sang songs. Ordinary people—everybody, really—sang songs when I was a kid. They knew the words to so many songs and would sing them, even if they weren’t great singers. So even if they weren’t great singers, people would sit around, have a few drinks, and if there weren’t any musicians around, they’d just sing to each other. It was a big part of my culture growing up.

My uncle was a very sophisticated musician—he played everything, had many bands, and was a brilliant singer. I can’t pinpoint my first live music experience because I’ve been going to see bands since I was very small. Then, when I was 12, I moved to Manchester with my family, already having “the music in me,” so to speak—the passion for it. At the time, I didn’t think I was going to make music, but I became obsessed with it—going to see live music in Manchester. Initially, it was bands like Sonic Youth, The Jesus and Mary Chain, The Butthole Surfers, Big Black, and Sub Pop—alternative music, basically. We were really into The Jesus and Mary Chain in particular.

As I got older, I started going to nightclubs. It was a great time in Manchester, especially in the late ’80s. There were all sorts of music scenes to experience—reggae sound systems, amazing Black clubs with RnB, soul, and hip-hop. Then house music came in, and with it, the raves. When I was 19, I moved to Sheffield. The reason was that my boyfriend was halfway through his architecture course there and had to return to finish it. So, I moved with him.

For the first year, I spent many days at his university, attending crits, talks, and getting really into architecture. My first tour of Europe was actually with him, and it was an architectural tour. We planned a six-week trip around Europe, looking at different pieces of architecture, so I learned a lot from him.

Sheffield was full of self-starters. It had a very DIY scene, where it was hard not to meet people involved in music—people starting record labels, nightclubs, parties, record shops, and building studios. There was also a great design practice called Designers Republic, which did all the record sleeves for Warp Records initially. It was a wonderful place to immerse yourself in music and culture, so naturally, being obsessed with music, I got involved.

However, I never expected to become a singer or musician. That happened accidentally.

Oh, really? You never thought about it after hearing your voice? You never considered it?

Well, I did sing as a child in Ireland, but everyone sang, so I told you that—absolutely everyone sang. There was nothing unusual about having one or two songs you could sing when everyone else was singing. Being into more alternative music, and later, Black music as well, I felt like my little, undeveloped voice wasn’t interesting. I thought I’d end up doing something more visual.

If you’d asked me at any point during my childhood or adolescence, I probably would’ve gone through all these different phases. One day, I’d say, “I want to be an artist,” and another day, a filmmaker, or maybe a photographer, interior designer, graphic designer, or even a fashion designer. You know? But it was always something visual—that’s what I thought I’d end up doing.

Then I met Mark Brydon in Sheffield, and we fell in love. He was a very experienced producer, 13 years older than me. The first night we met, I recorded this line: “Do you like my tight sweater? See how it fits my body.” I did things like that occasionally at the beginning of our relationship—just saying stuff or pretending to be someone else, and he would record it and put it on a track.

That eventually developed into a handful of tracks, and then someone wanted to sign us. It was ridiculous—the most ridiculous thing! But he was happy to go along with it. I couldn’t believe someone wanted to sign a record deal for that. But I think because he was so experienced, he found it refreshing to work with a novice, someone who didn’t know what they were doing, wasn’t a professional musician or singer.

It was like starting from scratch, completely open-minded, where anything could happen. I learned to sing after I got the record deal, really. Sheffield was all about that development for me—developing myself as a singer, songwriter, and artist. I stayed in Sheffield for almost 10 years, and then I moved to London at the end of Moloko. I spent 10 years in London, and that’s where I truly came into my own as a complete artist. I started to manage the entire creative process as a solo artist, being very involved in and creatively directing everything connected to my records. I began to direct videos as well.

It’s all there—all the places I’ve lived and all the phases—they’ve all been really interesting, really an adventure. I’ve always been more interested in the adventure of it all than in making a big plan or being particularly ambitious. I’m ambitious about having an adventure more than anything else. I also feel like I’m more comfortable, in a weird way, when I’m not comfortable. I know I’m on the right path when I’m going beyond myself, doing something I’m not sure I can do. Even if I fail, at least I know I’m on the right path, methodically.

Yes, we need to be careful. When we fall in love with something, we need to make sure it’s something we’re committed to for the rest of our lives.

Yeah, well, it’s great. I’ve made it so that it’s not a narrow thing. I’ve made it so I can be creative in many fields, and that really suits me.

You mentioned also that you have a strong connection with your family and that they support your music career.

I think they were surprised that I did anything with my life [chuckles], so they were very pleased that I have a career. Yeah, my family is very supportive. My mother really understands my creativity, especially the weird and different aspects of it. She really supports that and understands me better than anyone else in my family. She always believed in me being different, outlandish or weird, or whatever way you want to call it. She’s always believed in me, in my gut instincts, that way. She’s a very intelligent woman, my mother—very sensitive creatively, sensitive to art, to beauty… Very… yeah. And you know, she understood it completely. Sometimes my father might be scratching his head a bit, thinking, ‘What’s she doing now? Why’s she dressed like that?’ Things like that, but still very proud of me.”

Cool, thank you. You spoke about the journey—if you could tell us about the process, the start of Moloko, and then your solo albums, all the collaborations, piece by piece?

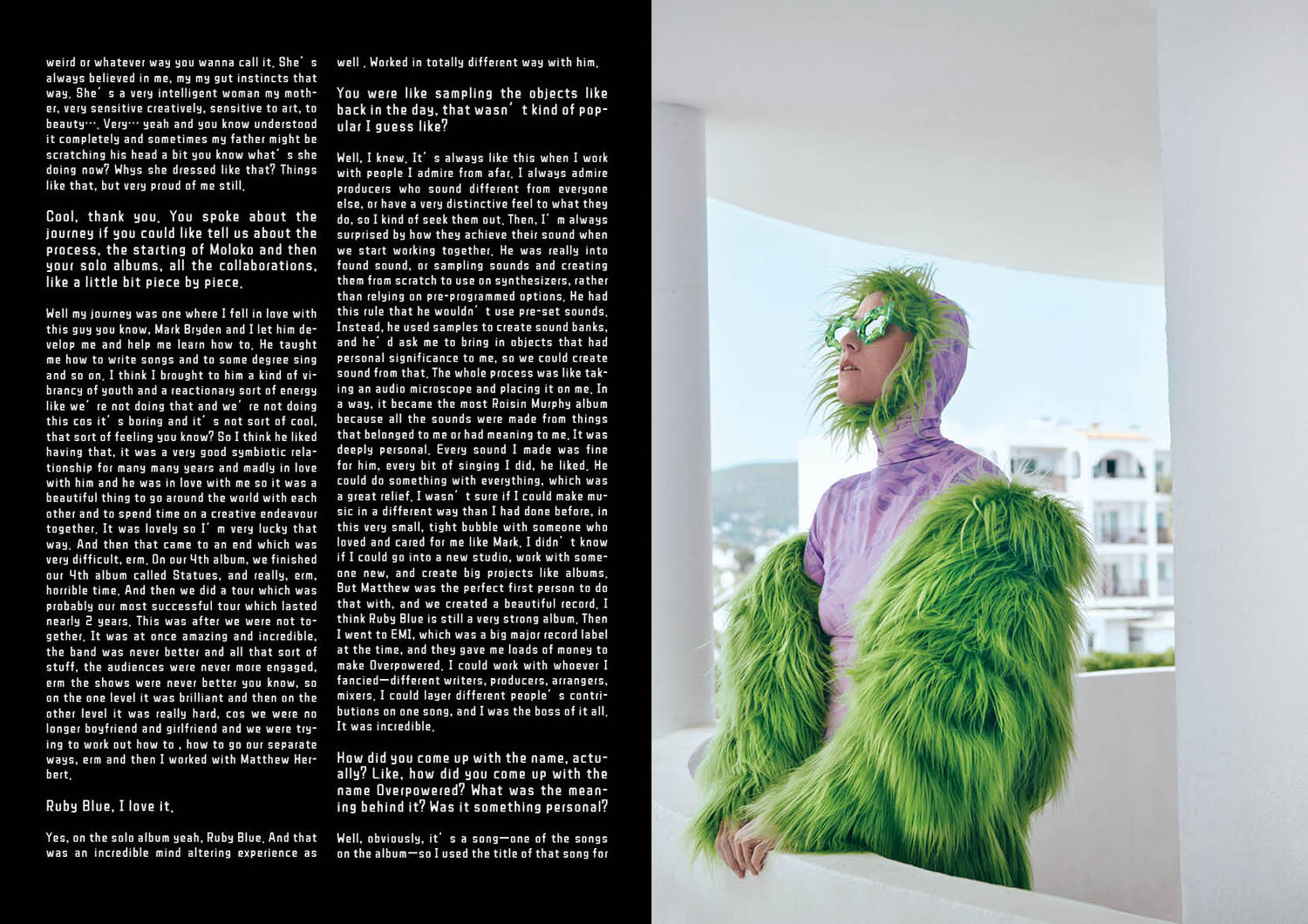

Well, my journey was one where I fell in love with this guy, you know, Mark Brydon, and I let him develop me and help me learn how to make music. He taught me how to write songs and, to some degree, how to sing and so on. I think I brought a kind of vibrancy of youth and a reactionary energy—like, “We’re not doing that, and we’re not doing this because it’s boring, and it’s not cool!” That sort of feeling, you know? So I think he liked having that energy around. It was a very good, symbiotic relationship for many, many years. We were madly in love, and he was in love with me. It was beautiful to go around the world with each other and spend time on a creative endeavor together. It was lovely. I’m very lucky that way.

And then that came to an end, which was very difficult. On our fourth album, Statues, we finished it, and it was a horrible time. We then did a tour, which was probably our most successful tour, lasting nearly two years. This was after we were no longer together. On one level, it was amazing—the band was never better, the audiences were never more engaged, the shows were never better. But on the other level, it was really hard because we were no longer boyfriend and girlfriend, and we had to figure out how to go our separate ways.

After that, I worked with Matthew Herbert.

Ruby Blue—I love it.

Yes, Ruby Blue. That was an incredible, mind-altering experience too. We worked in a totally different way.

You were like sampling objects—back in the day, that wasn’t popular, I guess?

Well, I knew. It’s always like this when I work with people I admire from afar. I always admire producers who sound different from everyone else, or have a very distinctive feel to what they do. So I kind of seek them out. Then, I’m always surprised by how they achieve their sound when we start working together. Matthew was really into found sound—sampling sounds and creating them from scratch using synthesizers, rather than relying on pre-programmed options. He had this rule that he wouldn’t use pre-set sounds. Instead, he used samples to create sound banks, and he’d ask me to bring in objects that had personal significance to me so we could create sound from that.

The whole process was like taking an audio microscope and placing it on me. In a way, it became the most Róisín Murphyalbum because all the sounds were made from things that belonged to me or had meaning to me. It was deeply personal. Every sound I made was fine for him. Every bit of singing I did, he liked. He could do something with everything, which was a great relief.

I wasn’t sure if I could make music in a different way than I had before—in that very small, tight bubble with someone who loved and cared for me like Mark. I didn’t know if I could go into a new studio, work with someone new, and create big projects like albums. But Matthew was the perfect first person to do that with, and we created a beautiful record. Ruby Blue is still a very strong album.

Then, I went to EMI, which was a big major record label at the time. They gave me loads of money to make Overpowered. I could work with whoever I fancied—different writers, producers, arrangers, mixers. I could layer different people’s contributions on one song, and I was the boss of it all. It was incredible.

How did you come up with the name Overpowered? What was the meaning behind it? Was it something personal?

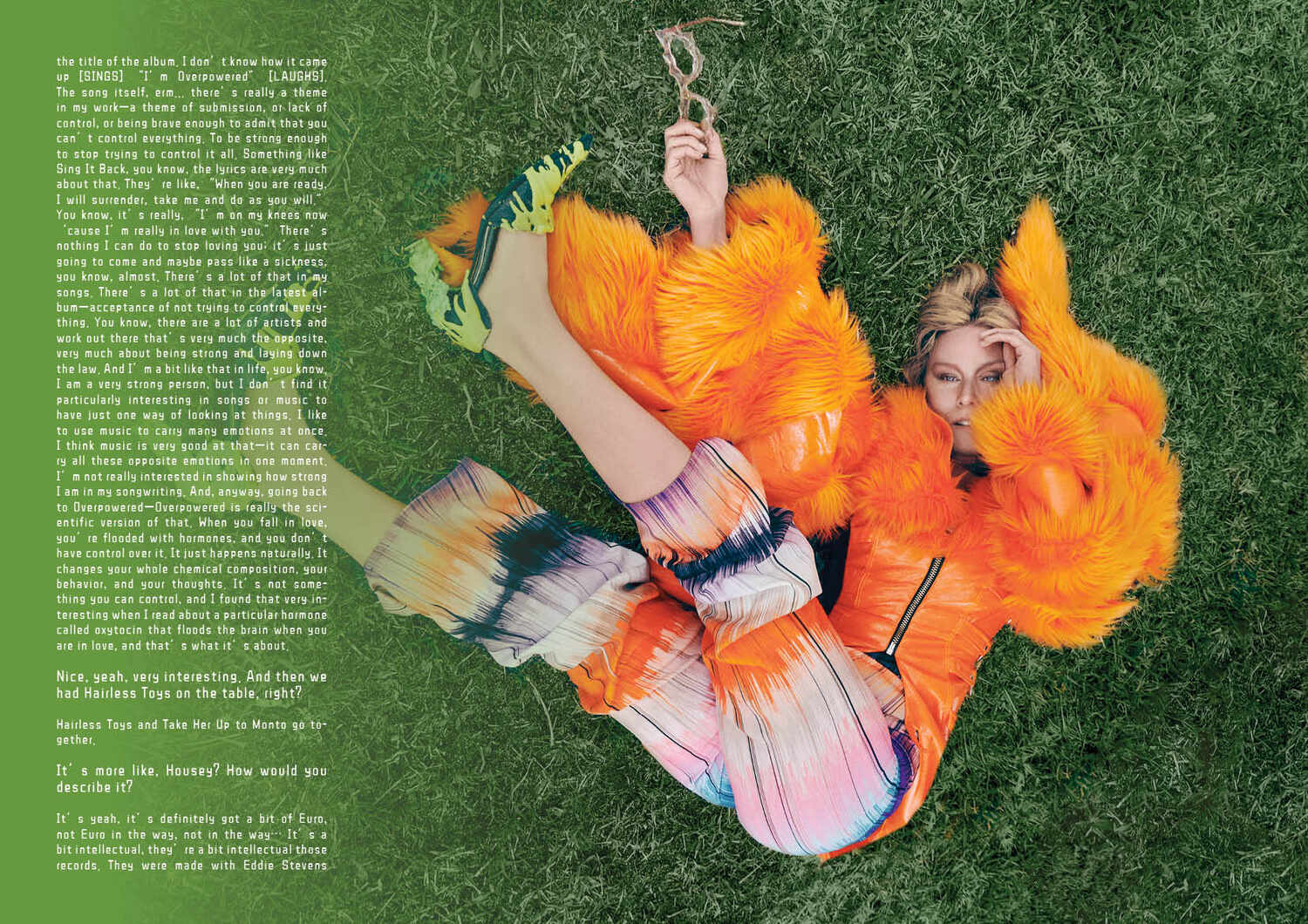

Well, obviously, it’s a song—one of the songs on the album. So, I used the title of that song for the album. I don’t know how it came up, but the song itself… there’s a theme in my work—of submission, or lack of control, or being brave enough to admit that you can’t control everything. To be strong enough to stop trying to control it all.

Something like Sing It Back—you know, the lyrics are very much about that. They go, “When you are ready, I will surrender, take me and do as you will.” It’s really about, “I’m on my knees now because I’m really in love with you.” There’s nothing I can do to stop loving you. It’s just going to come and maybe pass like a sickness, you know? There’s a lot of that in my songs. There’s a lot of that in my latest album—acceptance of not trying to control everything.

There are a lot of artists and works out there that are the opposite—very much about being strong and laying down the law. And I’m a bit like that in life; I am a very strong person. But I don’t find it particularly interesting in songs or music to have just one way of looking at things. I like to use music to carry many emotions at once. I think music is very good at that—it can carry all these opposite emotions in one moment.

Nice, yeah, very interesting. And then we had Hairless Toys on the table, right?

Hairless Toys and Take Her Up to Monto go together.

It’s more like housey? How would you describe it?

Yeah, it’s definitely got a bit of Euro—well, not Euro in the way… it’s a bit intellectual, those records. They were made with Eddie Stevens, who’s my musical director live. Very important figure in my life creatively—maybe the most important—because you know, you can make these esoteric, electronic albums, but if I hadn’t had him, I think it would have been difficult. He’s been my MD for 28 years, and even in Moloko, he was MD. Even with the records we made in Moloko, they weren’t easy to translate into a band and into a live experience.

But I think if you can make interesting records and then make live experiences that are exciting and interesting, and reflect the records clearly, that’s probably what’s kept me here. I’m still here because of that. If it was only the records, I think I would’ve disappeared a long time ago. I wouldn’t have been able to keep interest either. I wouldn’t have developed in the way I have as an artist if I wasn’t living this seasonal life—”Now I’m in the studio, concentrating on an album; now I’m touring for a year, a year and a half, two years, and then I’m back in the studio.” It’s a good balance.

They’re very different disciplines, but really, they’re two sides of the same coin. And if you don’t have both, I can’t imagine you can have a 30-year career like I’ve had. He’s been the key to that because he can take these weird records—these electronic records, whatever they happen to be, dance records—and translate them across a band, making them happen live. And it’s really live, where the band interacts, and things can go wrong.

Sometimes you wonder why. You play festivals, you play a great gig, everybody’s happy, the audience is clapping, but then a DJ comes on, and it’s like… they put a stick in, and the whole field goes berserk. They go mad for it because, for many people, it’s too much to concentrate on live music. It’s not as instant, not as balanced. The sound coming off the stick is always the same. The balance between the bass, the highs, the mids, the lows—it’s all done, and you just put it on. For many people, that’s easier to enjoy than live music.

But I still won’t give it up. I’m never going to give up that live experience. It’s just very special.

I think now it’s going to come back more for DJs to play live because the DJ scene itself has become very overcrowded.

RM: Yeah, but people love it—I mean, they literally love the sound of music going on, being loud.

G: But it’s a different sound live.

RM: It’s a different sound live, and it’s harder too.

G: Hard to beat that.

RM: Well, it’s hard to beat that, but you sort of need to know about who’s playing what to enjoy it.

G: Yeah.

RM: A lot of people don’t get it; it’s just over their heads. That’s a simple fact. You need to understand who’s playing what—the bass player’s playing the bass, the drummer’s over there, and someone else is doing that. You kind of need to have an understanding of the scope of it for it to be truly enjoyable.

G: Totally. And then you released two albums with the same label, Play It Again Sam. What’s the story behind that? How did that come about?

RM: The two albums were made at the same time.

G: Yeah, okay, yeah.

RM: So it was all recorded in one go. Nowadays, I usually just do one album per deal—one moment, one deal, you know? It’s like I make the record first, and then I find a record contract for it.

RM: And then I go off free again and do the next thing. But there’s still no pressure to record quickly; you can take your time and have breaks in between anyway.

RM: Yes, there were certainly breaks between Overpowered and Hairless Toys because I had babies, and other aspects of life took over for a while.

G: And then after that came Róisín Machine.

RM:Róisín Machine really started a long time ago because I did “Simulation” with Parrot 12 years before I released the album. So, that process began long before. Parrot is someone I’ve known since my Sheffield days—I’ve known him for about 30 years now. Occasionally, I’d make tracks with Parrot over the years. “Jealousy” was another one we released many years before the album came out, and then there were tracks like “Incapable” and “Narcissist,” which were also released before the album was fully completed. That album developed over many years. Then we made a remix album of it called Crooked Machine.

RM: I would describe it primarily as a Sheffield record. It’s got the sound of Sheffield—it’s got a hardness at the bottom, like a disco with this hard Sheffield steel feeling, and there’s a rigor to it. That’s very much Parrot’s style, you know. He’s very rigorous; he’ll just remove and remove and remove until you get down to the essential elements. He’s a visionary producer who can really imagine the room where the music will be played because he was a DJ for a long time, although he lost faith in DJing years ago. Back during the early days of the house explosion in the UK, he was a big DJ, so he understands that. These rooms he imagines, though, are kind of too cool for reality now, but they still exist in his imagination, and he makes music to fit those rooms.

G: And if we take all the albums you’ve made and compare them to the last one you released on Ninja Tune, how would you describe the difference?

RM: Well, it’s not really comparable, none of them are really that comparable. Only as a sort of development.

G: Okay.

RM: I think there is development for me. Keep going on the journey.

RM: The song, the singing, and certainly with Hit Parade, I began—along with a bit of Róisín Machine since they worked hand in hand and were in tandem for a while. I was working on both at the same time. I recorded most of Hit Parade myself, including the vocals, using music software, which was a new experience and a significant development for me. It made me, as I mentioned, very prolific and allowed me to work on two or three albums simultaneously.

G: That’s a lot, it’s intense.

RM: It’s not intense—well, it is, but it’s a different kind of intensity. It’s not like you’re working on an album, going in every morning at 11 o’clock and leaving at 7. Instead, it’s more like you can record whenever you feel like it because it’s always there.

G: When you get the inspiration?

RM: Yeah. I mean, Stefan—DJ Koze—who I made this album with, was the one who suggested that I use the same software he uses because he knew we wouldn’t be together much. He preferred to work on his own and have me send him stuff. That’s how he’s more used to working. So, he really encouraged me to learn how to do it. He said, “You’ll just be hoovering, and you’ll have a little humming sound in your mind, and then you can go straight to record it just like that.” And it’s true, you know? It turned out to be very true. It was great, especially because we hit the pandemic while making this record, and I was already up and running in such a way that it didn’t stop me from finishing what I needed to do for Hit Parade.

G: Okay, yeah. That’s great, very impressive. I was also interested in how, when you implement disco, pop, or electro into your songs, what resonates the most with you? How do you get your inspiration when it comes to blending those genres?

RM: With Parrot and Róisín Machine, we knew what we were doing. He’s very visionary, so he’ll decide, “We’re doing this, and it’s going to sound a bit like this in the end—like X, Y, or Z.” And then it does, yeah? But with Hit Parade, nobody had any idea how it would end up sounding. The process with Stefan is different. I think it’s more like he chips away at a piece of rock, like a sculptor, but without necessarily planning it out. It’s more abstract. Parrot, on the other hand, would say, “Okay, I’ve found a piece of rock, and I know there’s a man with a disc inside it, and he’s going to throw it.” He can see exactly what’s inside, with the right dimensions, and he knows how to get there. For someone like Stefan, though, he has to work with the rock, discovering what it is along the way. He has to be careful not to chip off a piece that makes the whole thing fall apart in the end [LAUGHS]. Otherwise, it might end up in the bin. So, it’s a totally different process. Does that sculpture analogy make sense? Stefan is fascinating because his ears are so incredibly sensitive. They’re always open. It must be exhausting—always alive to the critique of sound. That’s why there aren’t many people capable of doing what he does.

G: Yeah. You work with many talented producers. How does it typically start for you? Does it usually begin with a friendship?

RM: It does. It normally starts with some sort of connection.

G: Okay.

RM: Emotionally, friendship-wise, life-wise. Even, you know, starting with Matthew Herbert who had done some remixes for Moloko over the years, and I had sung with Matthew when he was DJing and stuff like that over the years, and there was this connection, and he always said that we should work together. And there he was at the end of Moloko, you know, at the end of the end of the end of Moloko when nothing and only wind was blowing in my life, you know, there was Matthew. And then obviously I’ve said that Parrot was best friends with Mark from Moloko, so I’d known him for many, many years. Mark from Moloko was my boyfriend—was my lover before anything, and you know, Stefan asked me to contribute to his album a few years ago, many years ago now, so 7 or 8 years ago. And then he enjoyed that, the way we connected, and he said, “I’d like to make a record for you now.” You know. And it just so happened that I was the last person to put anything on his album. And I think he was literally like, “Well, what am I going to do now? I’ve got nothing to do. I’ve finished my album. I’ll just give these other tracks to Róisín.” I happened to be there, you know. I feel like, I feel like, you know, I live, I breathe, and the work comes out of that.

G: And you enjoy it.

RM: And I enjoy it, exactly. I enjoy it.

My grandmother was very stylish, yes. But she was also a very powerful woman. Her husband died young, leaving her with three businesses to run: a fish and chip shop, a café, and a snooker hall—snooker tables were a big thing in Ireland. So she had to be the boss. I grew up seeing her as the big boss woman. She always wore a fur coat, leather gloves, and red lipstick, and her hair was always done. She was a powerful figure, my Nanna.

I guess that also affected you in terms of music and performance. What do you think about the strong connection between fashion and music?

Yeah, I mean, I’m hugely influenced by Grace Jones as well. I remember the first time I ever saw an image of her on the cover of Private Life, a compilation album. She’s standing on one foot with a mic in her hand, and the image is slightly elongated. You can’t see where it’s been altered; it’s seamless. Her arms and legs look just a bit longer than they should, and the lighting and airbrushing make her look very unreal. It was on someone’s fireplace mantelpiece in Ireland, and everyone who saw it would ask, “What is that?” I was just a child, and I was absolutely mesmerized. Was it a man, a woman, a statue, a drawing, or even an alien? It raised so many questions. Nobody had ever seen anything like it. She has created some images that no one has ever surpassed. I saw her perform live many years ago and was blown away by the simplicity of her performance. It was just one or two lights, a set of steps, and her—yet it was the most dramatic thing I’d ever seen.

More recently, I’ve come across some mid-century Italian divas, particularly MINA, who also made me feel validated. I thought, “Okay, this is the type of artist I am.” Even though I didn’t know about her before, her work resonated with me. She had an album cover where she wore a beard—something nobody had ever seen before and still hasn’t. It remains one of the most challenging and unusual images. All these artists who have influenced me share a sense of humor and wit. They don’t take themselves too seriously. They show that you don’t have to be always serious to be taken seriously. I very much feel the same way.

Yeah, your icon status spans decades, but was there a specific breaking point or moment when you knew that—do you remember that moment?

RM: No. There’s no point where…

G: There is no point? Really?

RM: I never knew anything. And I don’t know whether I will be remembered, or if the music will be remembered, or if I have total financial security.

Okay, going back to fashion for a moment: you also performed at a Viktor & Rolf show. What are your experiences with Dutch designers?

RM: That was one of the most dangerous things I’ve ever done in my life.

G: Oh really?

RM: Yes, I was seven months pregnant, standing on something a little bit bigger than this but very, very tall, wearing a very heavy gown. Those tulle dresses look light, but because there are so many layers, they’re super heavy. I was also wearing these big stripper shoes. I had to sing on that, thinking, “If I fall off, I could harm the baby, and it could be over for me. Maybe I’d die too, and I’d be in front of the world’s press.”

It was probably one of the hardest 15–20 minutes of my life. When I came off stage, I went outside and sat on a park bench with my friend Simon and burst into tears. I cried uncontrollably from the stress and hormones that had built up over the last couple of days. Preparing for what was essentially a brief but intense performance felt like bad sex compared to the two-hour Róisín Murphy shows. Yet, it was such a beautiful show, and I’m so happy I did it. Looking back, it’s a stunning piece of fashion art.

Also, Viktor & Rolf’s shows are the most dangerous. I have some really risky stories involving their designs. For example, during the Overpowered era, I wore a dress with an internal lighting rig and sound system. To accommodate this, I had to wear a steel frame strapped underneath the dress, which was pinned to a massive rig. I shot this on a high street in the UK because Overpowered was all about juxtaposing glamorous fashion with mundane daily scenarios. It was windy that day, and the dress acted like a sail. Inside, it was so heavy that I nearly fell over several times, and people had to catch me. If I had fallen, it would have been very bad.

And recently, you also collaborated with Emilio Pucci. What was the story behind that? Did you go on your own?

RM: Recently? Yeah, we just went to Rome—the whole family went. The story is that Camille, the creative director of Pucci, really likes me. She came to my show in Milan recently; she’s a lovely person. They used my version of Pensiero Stupendo for their show in Rome. Camille invited me and put us up in five-star luxury. It was such a fantastic experience for us all. I didn’t have to do anything; I didn’t even have to sing. I just went to the fashion show, they played my music, and we got to stay in Rome for a few days. It was wonderful.

And one more question: in Berlin, we have a lot of intimate basement shows, but you also perform for huge crowds. How do you manage to navigate and adapt between these different types of performances?

RM: No, I like the basement thing. Personally, Sheffield was always about basements—small parties, small free events. Those are the times I look back on with great fondness. The time spent in Sheffield was like being part of a family, creating our own culture and doing it ourselves.

Cool, yeah, awesome. Do you have any plans for new videos? As you’re also a director and have done a lot of videos yourself, I’m curious if you’re working on any upcoming projects.

Yeah, I’d love to make more videos, but there isn’t as much demand for spending a lot of money on pop videos these days. People tend to prefer watching behind-the-scenes content or real, candid moments—I actually got in trouble recently for posting a bit where I was farting! It’s hard to convince people to invest heavily in pop videos now. I’d love to direct more, and not just music videos but other types of projects as well, so we’ll see.

Cool. And the last question: as our magazine is bilingual with roots in Asia, what are your thoughts on this part of the world? How do you view the bridge between Western and Asian cultures?

RM: I don’t know much about Asia at all. I haven’t traveled extensively there.

G: Would you like to have a tour and plan?

RM: Oh god, yeah. I’d love to. I’d really like to travel in China and see what the story is, because it seems so unbelievably powerful and important in the world, and yet so hardly understood at all.

RM: Yeah.

G: I think definitely that would be amazing, and people would love you there.

RM: I’d love to go. Just even to travel, just to try and understand.

G: Yeah, we are going to have a tour soon with the magazine.

RM: Are you?

G: Yeah. We’re going to Seoul, then Tokyo, Shanghai, and then we are going to Hong Kong and back to Seoul.

RM: Amazing.

G: So maybe next time you could be a part of one.

RM: Yeah.

G: Yeah, I think so. Thank you so much.

RM: Thank you.

Interview: Grzegorz Bacinski

Production: KEYI MAGAZINE

Photo & Styling: Keyi Studio WWW.KEYI.EU

Izabella Chrobok & Grzegorz Bacinski

Makeup & Hair : Servulo Mendez

Assistant: Sean

More fashion content -> Click here

more fashion features here

Our next event : ELSE – Berlin – 29.05.2025